The term Utopianism has lost its merit in the eye of society and has become associated with wishful thinking, implausibility, and irrelevance. Modern political thinkers are very unlikely to engage in discourse on the constitution and economy of a theoretical place, whose very name means ‘nowhere’ and whose construction involves such imaginative speculation, and would rather focus on pressing contemporary issues; they rightfully reject Fourier’s sea of lemonade and other utopic thought experiments as a waste of their time.

Some would even argue that the very idea of a perfect society would be counterproductive; Voltaire hinted at his opinion that such discussions are moot when he wrote that, after reaching the utopia of El Dorado, Candidie chose to leave out of sheer boredom. Orwell expressed his scepticism regarding people’s ability to imagine happiness except in terms of contrast, and found the most appealing description of Heaven to be that of Tertullian, in which enjoyment is drawn from observing the torture of the damned. Swift’s description of the Houyhnhnms is tepid and uncompelling.

Such feelings of impatience with the topic and of preference to pragmatism are understandable, but they are also dangerous. No winds are favourable to a sailor without a destination, said Seneca; if we value the opinion of that great thinker, we must agree that political discourse requires a goal in mind. In this regard we may agree with Oscar Wilde’s statement that a map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth glancing at.

The discussion on utopia ultimately boils down to a discussion on values and standards; as with all philosophical discussions on ethics, its purpose is to differentiate good from bad and provide an example to test our hypotheses. But utopian thinkers, such as Plato and Thomas More, erred when they attempted to provide too specific examples and too rigid standards for political success. Plato’s attempt to restrict music to specific modes, for example, defeats its own purpose, just as More’s description of the Utopians’ treatment of slaves renders his theory obsolete and absurd to the modern reader.

For that reason, we shan’t attempt to spell out the particular details of a perfect society. Nor shall we express support for any form of Utopian Social Engineering, but we shall, nevertheless, attempt to delineate the features of utopia so as to better understand our political desires. In De officiis, Cicero chastises those who neglect their civic obligation and do not attempt to share their thoughts with the populace. In that case, I will attempt to illustrate some version of the perfect society that I deem desirable.

We must nevertheless take care to avoid one crucial mistake: whom should we have in mind when we speculate upon the concept of a perfect society? For whom should we design our utopia? The negligence of some thinkers regarding this question has directly led to modern impatience with the whole topic. One can hypothesize about utopianism in two distinct ways: the first method starts with the characteristics of society and leads up to the desired result, and the second method starts with a hypothetical optimal result and works backwards.

We can therefore differentiate positive and negative utopianism thus: one seeks to create a perfect society for humans as they are and the other seeks to do so for humans as they should be. In other words, negative utopianism invents the optimal system in advance, in a process of sedentary mental exercise, and sets out to perfect mankind to fit it. The second version of utopianism has rightly received our scorn, and so I shall attempt to deal exclusively with the first.

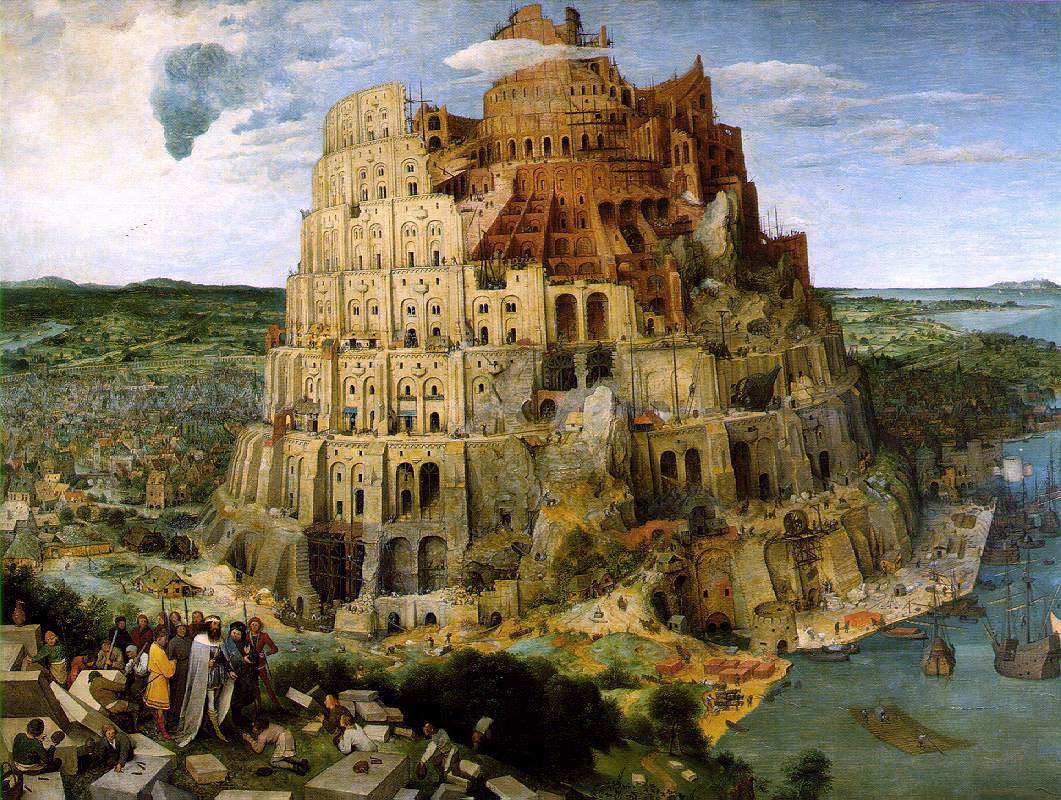

I believe that the observation of no more than three principles is required for such a discussion, namely: the meaning of life, human psychology, and the purpose of society. By focusing on those three principles, and by drawing whatever ancillary lessons that can be drawn from them, I hope to show what I believe to constitute a fair representation of a theoretical utopia, a slightly less pious version of Augustine’s Civitas Caelestis, so to speak. To reach a pragmatic utopia, a Civitas Terrena, we shall also examine some more specific values and policies.

To my mind, every affair or discussion begins with the question of the meaning of life. I seem to be doomed to gravitate towards that starting point, without which I cannot find the end to logic and a reasonable basis on which to lay my claims. Perhaps in this case I will attempt to state the matter rather unceremoniously, with little pomp and circumstance, so as to expel any sort of misunderstanding about it – although, admittedly, the crux of this idea can be found in the very many works of talented existential authors.

Once man came to grips with his reality and escaped the bestial urges of necessity, he was left with no choice but to face the core existential question: why live? The entirety of mankind has thus far come up with only four answers to that eternal question, namely: servitude, escapism, nihilism (which is arguably just a failure to answer the challenge), and existentialism. The last version concerns us most, for it is in fact the most logical one. The existentialist admits the lack of objective meaning, but chooses to use his faculties of reason to conjure his own subjective answer to the universal challenge.

Two important distinctions about this process must be made in the context of a discussion on utopianism: the difference between meaning and purpose, and the subjectivity of that kind of answer. In a different essay, I have likened meaningfulness to an internal warmth that a naked man feels in a blizzard; this meaningfulness cannot be adequately expressed, and it is definitely not akin to the concept of purpose, for purpose assigns meaning to an external factor. The person who seeks purpose seeks something for which to live, whereas the person who finds meaning can only exclaim ‘I live!’ and place himself as the ultimate goal, which is simultaneously sought and found. The political implication of this finding is that external pursuits are not necessary to the creation of meaning, and may in fact inhibit that creation by acting as red herrings.

As for subjectivity, we must stress the fact that meaning belongs to the individual. Any attempt to impose some form of meaning, regardless of whether it is a cogent answer to the existential plight, on another individual is an act of tyranny. We can immediately see that servitude, in the forms of religious or ideological belief, is antithetical to existentialism and cannot be reconciled with meaningfulness, for how can the individual conjure meaning when his faculties are assaulted upon by external impositions? Marx’s famous passage about the illusory happiness of religion comes to mind. Because meaning belongs to the individual, any form of collective identity or ideological zeal blocks the individual from attaining existential satisfaction. The only existential form of collective identity, as we shall see in the later stages of our Civitas Terrena, is the most basic one: human.

We have dealt in length with forms of escapism and shown the futility of such an attempt. To us, hedonism and alcoholism are equivalent; both inure the individual to his plight and assist him in forgetting the terrors of death and meaninglessness, but such escapist attempts remind us of a patient who refuses to be treated. In his attempt to evade necessary pain and hardship, the escapist causes immeasurable other psychological ailments that haunt him for the remainder for his life.

And indeed, we can find an equivalent to existentialism in psychology. We need look no further than the research of Abraham Maslow, who showed us the hierarchy of needs, for at the peak of that hierarchy one can find self-actualisation. What is self-actualisation but a psychological expression of Nietzsche’s Will to Power or of the ability to find inner warmth and meaning in the face of the void? And who can generate self-actualisation but the self? I conclude that this psychological finding affirms that the greatest good that can occur to a person is existential satisfaction through individuality.

We can now turn to the purpose of society and assert the following conclusions: firstly, the purpose of society is to serve the individual, and not the other way around as fascists believe. Secondly, to serve the individual society must facilitate his advancement along the hierarchy of needs. I do not consider that society should push the individual up the hierarchy – as we’ve established, that would be both paradoxical and undesirable – but it should at the very least contribute to the feasibility of his attempt.

We have now come, rather quickly, to the definition of our Civitas Caelestis, our theoretical utopia: a society in which self-actualisation is the norm. Such is the happy theoretical state of man, and no improvements can be suggested to it. I hope you’ll find this utopic suggestion sufficiently imperfect to avoid accusations of absolutism.

Of course, claims that do not hazard any disagreement are worth very little, and some might criticise me for staking too little when I say that utopia consists of self-actualisation and nothing more, but to those I only point out that this theory is indeed selective for its negation of collectivism, ideological and religious zeal, consumerism, hedonism, and nationalism. For the case of an impractical and theoretical utopia, self-actualisation suffices.

To clear the road to that utopia, and bridge the gap between reality and theory, we must delineate some of the less grandiose elements of our imagined society and dive into policy and values. We must ask ourselves which elements of contemporary politics have a place in our utopia and which do not, and thereby select the doctrines of the present to prepare for those of the future.

Thomas More did not fail to define the value of the utopians, who aspired to felicitas, or happiness, above all else. Indeed, happiness is the greatest measurement of society, and More desired it for good reason. In fact, every political ideology has the ultimate goal of happiness in mind, even if its ideologues sometimes mistake the forest for the trees by focusing on its suggested means rather than ultimate end. The libertarian cries for liberty for the same fundamental reason that the communist cries for equality: they both believe that their respective values are more integral to happiness.

Curiously enough, happiness is a weird creature against which argument cannot be held, for if we were to say we did not seek happiness but something else, then that other thing would simply become the source of happiness in our eyes. Nevertheless, the pursuit of happiness in a political setting can lead one to favour some grotesque lines of reasoning. In one of his debates, Sam Harris claimed that any policy or idea that pulls humanity away from the most horrible suffering of every single individual is desirable, and many modern thinkers subscribe to this way of thinking. But isn’t such an ethical system but another version of utilitarianism? Has Dostoevsky not cured us of our illusions regarding that oppressive ethical code?

We must therefore shy away from the direct pursuit of happiness, and acknowledge that we cannot impose our version of it upon another or justify the oppression of the few in the name of the gratification of the many. Ironically, we must neglect happiness and focus on the instruments that facilitate its creation without becoming ideologues; what, then, are those instruments? Which policies must we pursue to create a utopia on earth?

The first conclusion that I draw from my deductive reasoning is that, for all its flaws and imperfections, capitalism is the only economic system that can support a utopia. Some might accuse me of succumbing to capitalist realism, while others might point out the various forms of exploitation within the system, its inherent instability and tendency to create crises, and so on. All of those arguments are just and valid, and yet I must insist that only capitalism can lead us to utopia for two main reasons: identity and innovation.

Let us begin with identity; we have already explained why it is so crucial for existential wellbeing and how self-actualisation belongs to the self. The more an individual accepts external modes of identification, such as racial, nationalistic, or ideological belongings, the more he allows infringement upon his own constitution. That assertion does not mean, as some erroneously conclude, that the individualistic person has no opinion or culture, but rather that he feels no attachment or obligation to any of his preferences; his opinions are chosen critically, piecemeal, and his cultural interests are universal.

The staunch Marxist might argue that individualism is not restricted to capitalism, and that in fact collective ownership will release the individual from labour and enable individuality to thrive; in fact, Marx made the exact same point when he discussed leisure. But regardless of leisure, which we shall soon address, how can the individual hold an individualistic identity when his identity is restricted to class? How would an individual reach self-actualisation under the stringent identity-expectations of his fellow workers?

Another argument can be made against the nature of individualism within liberalism: does the liberal west really practice the individualism it preaches? Isn’t the modern individualist just as blind to his own identity when he conforms to hedonism, consumerism, and tribalism? Furthermore, isn’t individualism just a euphemistic version of selfishness? To those refutations we answer that modern manifestations of feign individualism betray their own purpose and are untrue to the philosophy’s core. Indeed, true individualism cannot be consumeristic and tribal, nor is it related in any form to selfishness. Individualism refers to identity alone, and does not in any sense warrant consumerism or negate sympathy.

Because individualism is absolutely crucial for self-actualisation and existential satisfaction, we must reject alternatives to capitalism and allow for the system that supports individuality most excellently. Whether we manage to overcome consumerism within capitalism, fix the system’s very many flaws, and reach a state of manifested social atomism remains to be seen, but any alternative would abandon the attempt from the start.

The second argument in favour of capitalism comes in the form of innovation, and more particularly automation; but before we embark upon the topic of innovation, let us attempt to define value. I have already explained the difference between the useful and the valuable, and have shown that valuable things cannot be useful, for they are more akin to ends than to means, whereas useful things are means by definition. The greater challenge comes in differentiating value and wealth, for those two things are more readily interchangeable.

Let us begin with defining the valuable, for I believe that it is the larger concept of the two. Value is, of course, an intersubjective construct, and one that can only be attributed to things based on the appreciation of humans. The first and greatest value, as has been observed by humanists, is humans, who hold intrinsic, undivorceable value. But other things also hold value. Art is extremely valuable because it is a form of self-actualisation, which, as we have established, is the greatest good for the individual and the purpose of society. Time is valuable because it is the medium in which human lives operate. Friendships are valuable because they fulfil a basic human need.

What, then, is wealth? Many economic researchers have preceded me in this discussion, but let us treat wealth as an instrument with which to acquire value. Wealth, in and of itself, is of no importance; its only purpose is to enable the exchange of valuable things. Wealth is an estimation of value that can be acquired by its means.

“The natural worth of anything consists in its fitness to supply the necessities, or serve the conveniences of human life.” Said Locke. A litre of wheat is worth its price for the estimation of value that can be drawn from that wheat in the form of human sustenance or enjoyment, but if the wheat turns out to be spoiled then its value is diminished regardless of the price paid for it. conversely, a simple thread proved invaluable to Theseus, just as a mere horse at the right moment was more valuable to Richard III than his whole kingdom. These instruments borrowed their value from the value of the lives of their users, which would have been lost without them; to Richard and Theseus, no wealth could have replaced the basic tools that facilitated their survival.

Wealth is but a gamble at value, an imperfect attempt to quantify something that is essentially qualitative. “An exchange value that is inseparably connected

with, inherent in commodities, seems a contradiction in terms.” said Marx. When man picks his hatchet and descend upon a forest, he wagers that the wealth of wood that he will extract from it will generate more value through its use than the current value of the forest, which stems from its contribution to the biophilic sentiment of mankind and its support of environmental wellbeing and biodiversity, which ensure human health and sustenance.

We have taken this detour to reach a conclusion about the value of labour, through which we shall prove the value of automation. Socialists are ever keen to discuss the value of labour and to point out that wages do not reflect the true value of the labourer’s efforts, but rather the parsimony and interests of the capitalist; their solution is to transfer ownership over the means of production to the labourer so as to circumvent the problem of evaluating that labour. If the value of labour is transferred to the business, infers the socialist, then the only way to equally distribute that value among workers is to split the value of the business among the workers.

Without considering the many practical economic arguments against such a suggestion, we can conclude that it is erroneous despite its benevolence, for it completely mistakes wealth for value. The true value of labour lies not in production but in the time invested. Some labour is necessary of course; every organism exerts effort to survive, and inaction is akin to death, which is very clearly undesirable, but there lies the limit of the value of labour – every minute that is spent on higher steps of the hierarchy of needs is more important than minutes spent out of necessity. In short, the optimal number of hours spent labouring for any individual is zero.

By labour I do not refer to work, and I do not suggest a social existence of pure lethargy. Labour is work that is done for the sake of another and out of personal necessity; quite bluntly, it is the reshaping of matter on the surface of earth or the supervision of the labour of others, who are physically employed in the reshaping of matter on the surface of the earth. Work, on the other hand, can be regarded as any activity for the sake of the self. Work takes the form of exercise, the creation of art, craft, studies, and so on; it is effort that is exerted without the need for compensation.

We can therefore conclude that wages are not an adequate compensation for labour, but nor is collective ownership and the wealth that supposedly comes with it; we must treat labour as a necessary evil, not as a desirable good, and seek ways to rid ourselves of it. By emancipating ourselves from forms of labour – especially manual labour, which causes such psychological harm to its labourers – we can focus on work that is more conductive to human happiness and to self-actualisation. Leisure is therefore a greater good than labour.

Perhaps in the present, wages are a less fair way of compensating labourers than equity or ownership, although arguably they are more practical; I leave that question to the economists and Marxist to decide. But for our purpose, we must conclude that wages are superior in the most important sense: they can lead us towards emancipation – the eradication of necessary labour from society.

The capitalist might be driven towards good by greed, but he is driven to good nonetheless; his interest is to replace as many workers as possible with automation and minimize his expenses on manual labour, and therefore he actively seeks to replace working hands with machinery. In the process, the capitalist unlocks powerful Schumpeterian forces and causes innovative disruption, thereby leading us to a society in which resources are more abundant (or at least more easily utilised) and in which corporate slavery is replaced by mechanical slavery.

In a society of great abundance, some form of regulated distribution might take place. Perhaps the idea of UBI will become feasible in the future, although I don’t think it can be practically implemented in the present. Some might point at the implausibility of reining the financial power of the rich and forcing such distribution through political means, and that may be true, but the idea is at the very least possible. We shall shortly explore the conditions for the existence of such a state, and what fruits we can expect the future to yield, but for now we must stress that the combination of automation and UBI is indeed fitting for a utopia.

With regards to socialism, even if we concede that innovation can occur under such a system, albeit more slowly, we must ponder the plausibility of replacement. Collective ownership implies collective power and involvement in decision-making processes, otherwise some form of injustice will remain in the system. In that case, will the labourer concede to his own replacement by machinery, or will he be more likely to vote against innovation and retain the status quo? Have we ever seen instances in which people chose beneficial innovation at the expense of their security? This barrier leads me to believe that true emancipation of workers cannot occur within socialism.

Arguably, socialists care more about equality than emancipation. But alas, what crimes are committed for the sake of equality, and what horrid vengeance does it demand of its ideologues! Had Mme Roland only lived to see the horrors of our days, she would have paraphrased her objections to the atrocities that were made in the name of liberty and focused on equality as well. And all this vengeance is dished by the supporters of equality for the sake of wealth, not value! We must now press the second conclusion we can draw from the difference between wealth and value, and show that wealth inequality can exist in utopia.

What is our concern with wealth inequality if society facilitates self-actualisation? As long as individuals can move freely within the near-perfect society, whose details we shall soon explain, and fulfil their psychological needs, what is the purpose of wealth equality? Wealth is but an estimation of value, and true value belongs to the individual; the only reason to desire excessive wealth is hedonistic pleasure, for one must continuously expend resources to remain on the hedonic treadmill, just as the main reason to resent persons who hold excessive wealth (provided that they acquired it fairly and use it judiciously) is envy.

In our utopia, individuals will be free to pursue self-actualisation with the means that the state will grant them. Personal endeavours will require very little wealth, for those endeavours will not demand grandiose affluence, which is after all just a compensation for lack of true value. The true Übermensch, whose constitution all but bursts with existential satisfaction and who is continuously employed in self-actualisation, cares not for riches and ornaments; his value erupts from within, and to him envy is but a compass that leads him to self-betterment. But why should the Übermensch envy the rich? What do they possess that is not an imitation of his success?

We have shown, through the definition of wealth and the importance of individual identity and automation, that the economic system that can support a utopia is none other than capitalism. We can now move to other matters and discuss the conditions that will lead to our utopia and the features of our perfect society.

Yuval Noah Harari has provided us with a cogent and compelling argument for the inevitable unification of the world; according to him, history is a tale of the merging of human societies, which have moved from an unimaginable plethora of small, simplistic cultures to fewer and fewer large, complex cultures. The trend of globalisation was driven by trade, conquest, and proselytism for thousands of years, and is now driven by travel, environmentalism, and the internet. We can safely conclude, according to Harari, that the world will eventually unify under one set of values and one common rule. In such a world, individuals will share only one form of collective identity: the feeling of belonging to a human body, and nothing else.

I do not know why some notable thinkers, such as Christopher Hitchens, preferred division to unity. Hitchens, despite his cosmopolitan sentiments, argued that all progress occurs through conflict, and that the very nature of politics is confrontational; but general unification does not negate discourse and civil conflict. In a unified utopia, pluralism and debate will occur without the need to resort to violent and destructive clashes, and within a framework of a unified humanity. At least in some regard, conflict and unity are compatible.

Through these lenses, we can conclude that the main contribution of conflict to progress is the determination of which values survive to see the new world order, but also that eventually a new world order will arise and unify the descendants of those whose values will have been vanquished under the banner of the values that will have triumphed. Personally, I would like to believe that the values that will emerge from that amalgamation are the values of the enlightenment, for that victory will symbolise the triumph of reason and enable us to live under the values that are most conductive to human happiness. Nationalism and other forms of tribalism will succumb in the end.

Some might say that tribalism is an integral part of human nature and that it cannot be left behind. I offer two arguments against that claim: firstly, the very concept of social existence requires the repression of some elements of human nature for the sake of social functionality. Arguably, such elements as violence and the tendency to theft are definitively repressed in modern societies, whose constituents are far more civil than the peoples of antiquity. Just as the laws of Hammurabi strike us as barbaric and crude, our tribalism might be scoffed at by posterity.

Secondly, we might find symbolic alternatives to tribalism; sport is the modern outlet to violence, and acts as a mostly innocuous substitution, albeit crude and boorish. People who wilfully choose to adopt such a collective form of identity bar their own way to self-actualisation, but we cannot impose individualism upon the populace as the architects of a utopia; we can only facilitate the spontaneous emergence of such noble constitutions within people, and hope that they will prefer individuality to tribalism. On a final note on human nature: technological advances might enable us to change our own nature, but such an argument borders too greatly upon indulgent speculation.

These, then, are the conditions for the creation of utopia on earth: world unification, the absolute triumph of the enlightenment, extensive automation, and the resolution of climate change (an issue far too severe for us to tackle in this text, but which we must overcome lest we perish – in which case a utopia will obviously not materialise). Under these conditions, conflict will no longer be necessary and politics will shrink to mere social maintenance. Fukayama might regard this view as yet another fantasy of statelessness; I therefore emphasise that political institutions will not be supplanted by either the governance of markets (championed by the right) or the spontaneous unity of the people (championed by the left), but will simply continue to operate without the constant strains of major political issues. In the absence of hardship, society will be free to perfect its institutions, stabilise its extraction of resources in a sustainable manner, and enhance the quality of its human capital.

All that remains is to account for the details of our Civitas Terrena; as we have mentioned, we cannot mandate the self-actualisation of its individuals, but we can construct the framework that will enable that boon. Indeed, the purpose of society is to create a framework within which to enable the operation of its individuals, who are ultimately responsible for their own fate. Any alternative to personal responsibility, however benevolent, is tyrannical. While in our modern societies the insistence upon ‘bootstraps’ mentality is dogmatic, because environmental conditions mount too many obstacles for the majority to succeed, the conclusion that people should be led by the nose to happiness is despotic. The main responsibility of society is to ameliorate those environmental conditions, not to mandate the lives of individuals.

Therefore, our utopia will only devise laws that delineate the limits of the individual, but it shall never require the individual to behave in a specific way; its regulations may forbid a person to incite to violence, but they shan’t demand the expression of certain words by law. Laws, like society, provide frameworks and limitations, and they operate in relation to negatives.

Regarding the legality of drugs, I must admit that drawing the line between social functionality and personal responsibility is extremely difficult. I do not know whether every substance should be made legal and distributed under the regulation of expert chemists, and I hope that future research will shed more light on what should be done to combat the social implications of some drugs.

The government of our utopia will most likely be some form of parliamentary democracy, although politics will likely be diminished to the scale of local governance and politicians will cease to play the role of leadership and become more akin to public officials, whose glory will be very slight. Perhaps when so little remains at stake, and the heat of politics and confrontation subsides, democracy will finally function properly and logically and libertarianism will become justifiable. At the very least, democracy is required to ensure that the government will not view its citizens as property.

Needless to say, healthcare and education will be subsidized by the state, and the latter will be completely secular. Such policies are so fundamental and necessary that any debate against them is almost ridiculous in our day and age, let alone in a utopic society. Regarding UBI, perhaps the future abundance of resources will finally make it feasible, whereas today we apparently lack either resources, sustainability, or social stability to afford it, for conflict and environmental hazards cause us great expenses. I remind the inventiveness of man in the face of scarcity to those who might claim that resources are finite and more likely to diminish than grow; throughout history, man has created more resources than he has exhausted.

What will be the nature of the life of our utopian? He will grow up in the house of his parents and live according to their wealth, but even if his family is extremely poor he will at the very least live in a condition of zero necessity. The state will provide its individuals with minimal essential services, such as plain food, shelter, electricity, and sanitation, and thereby the individual will be emancipated from labour and free to pursue his self-actualisation.

Should the individual desire comfort and pleasure, as I expect many will, he will have to employ himself in labour and earn wages, with which he may purchase whatever he so desires. Such labour will be truly fair and just, for people will not be driven to it by necessity but purely by desire and free will. The labour of those educated individuals will consist mostly of tasks that cannot be performed by computers and of maintenance of the means of automated production. This form of labour will ensure the continuous functionality of machinery and provide the state with the taxes it will require for its operations. Naturally, no form of discrimination will take place, and individuals will be free to pursue their career of choice and succeed according to their merit. Perhaps when all of our conditions are met we will finally enable equality of opportunity and create a meritocracy, but equality of wealth, as we have mentioned, is out of the question.

With the remainder of his time, or the entirety of it if he so chooses, the individual will work towards self-actualisation at his own leisure; he will develop habits that suit the number of hours he is willing to work, and fulfil himself in whatever way he sees fit: sport, art, science, social exercise, travel, craftsmanship, and so on. In this state, the individual will truly be free, and the attainment of his happiness will be his personal responsibility.

One must admit that none of the ideas which have been suggested in this text are novel or original. If we manage to overcome climate change and hedonism, we need only divert our attention to automation, globalisation, rationality, and welfare to bring about a utopia on earth within several centuries. Let us hope that the many obstacles in our path are less severe than they seem to be.

Allow me but one more thought experiment, dear reader, to negate an alternative utopia. Hedonism is the pursuit of corporal pleasure, or the secretion of such chemicals as dopamine and serotonin in the brain. To a hedonist, the meaning of life is the production as much of such chemicals as possible. Imagine, then, some sort of farm of human brains that are attached to machines that balance the perfect chemical conditions for those brains to experience complete and everlasting euphoria. Would this farm of dissipation not be the perfect hedonistic society, in which the maxim ‘ignorance is bliss’ would be experienced literally?

Now ask yourself, which utopia would you prefer: that of the existentialist or that of the hedonist?