Slavery; what a disdainful notion today, and yet what a commonplace one in the past. Slavery as an institution dates back to the days of Hammurabi, whose laws deal severely with one who would aid an escaping slave. However, as we all know, slavery has not long been unconventional. For example, with what unflinching alacrity did Robinson Crusoe name himself ‘master’ after saving the savage Friday, and that in the presence of no other human beings! He could have just as easily made Friday a slave without teaching him that word. But in the age of Defoe hierarchy of races was presumed to such an extent that Crusoe, after 25 years of solitude, believed it natural to give himself that name. That anachronistic mode of thought also convinced Defoe that Friday would be delighted to sell himself unconditionally to the exalted European.

Happily, Fukayama was right. Some parts of history are gone and past, never to be repeated, at least in western civilizations. For who can today sustain the order of rank imposed by Aristotle, now that equality of opportunities* has proven no race to be inherently superior? Progress has proven what now seems obvious – slavery is achieved through force, not through ‘natural superiority’.

But, is slavery devoid of advantages to humanity? Properly examined, that claim could not be made even by the most liberal of minds, nor is it agreed upon by writers. Being myself in favour of worldwide liberty, I cannot but acknowledge and review the once lively debate this issue had aroused.

*Do not hasten to provide examples of inequality of opportunities in western countries, of which I am well aware. Although far from perfection, equality is more abundant than ever before, and has gone far enough to prove my point. The lack of perfect equality, in spite of which individuals in minorities still succeed, only strengthens my claims.

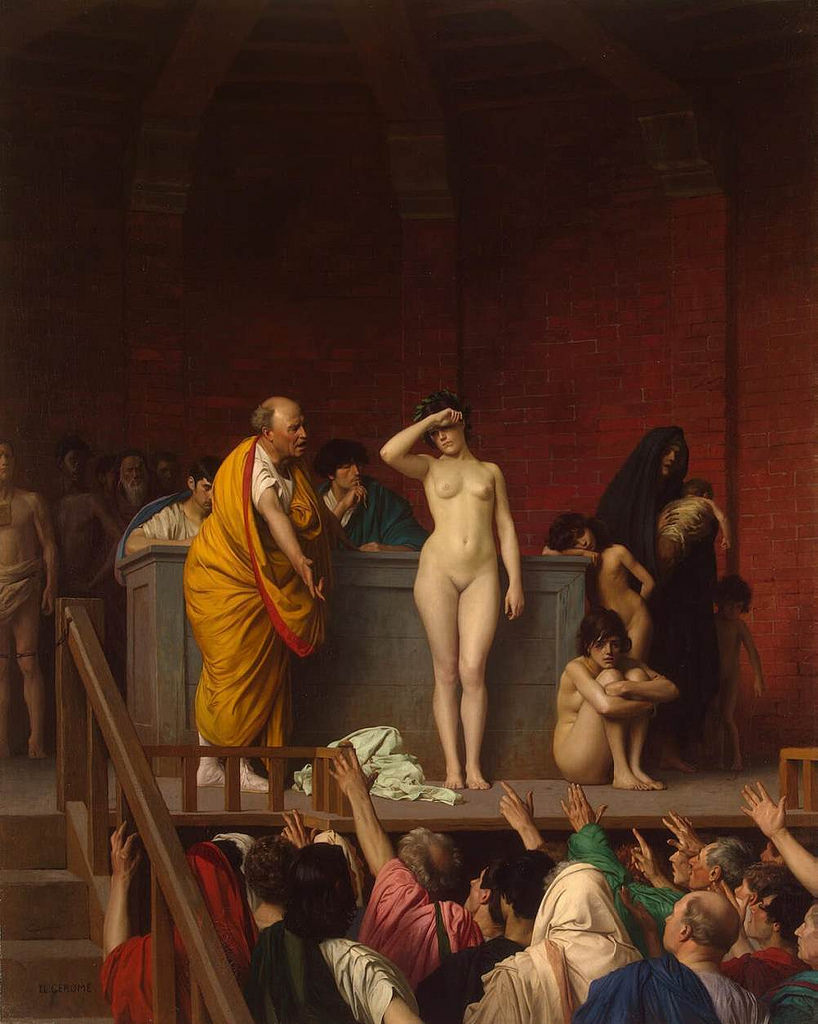

Slavery in Antiquity

Since slavery is an anachronism born in ancient times, even in prehistory, it is there that one must naturally begin one’s study. The most authoritative voice we can refer to when dealing with the slavery of the ancient era is Aristotle. No other philosopher since Aristotle succeeded in so completely laying down the modes and norms of his era. Metaphysics, ethics, politics, physics, biology, and astronomy were all touched by his hand and dramatically influenced.

In his Politics, when dealing with slavery, Aristotle quite calmly argues that human beings can and should be ranked according to race. Entire races are born to nothing but subjection, their inferiority rendering them incapable of sufficing their needs of life without a master to point their way. According to him, the system of slavery provided mutual benefits for both master and slave.

But is there any one thus intended by nature to be a slave, and for whom such a condition is expedient and right, or rather is not all slavery a violation of nature? There is no difficulty in answering this question, on grounds both of reason and of fact. For that some should rule and others be ruled is a thing not only necessary, but expedient; from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule.

It is no coincidence that the word ‘barbarian’ derives from ancient Greece, in which it originally signified one who does not speak the Greek language, and is therefore inferior in arts and mind. Such a dichotomy enabled the ancient Greeks to regard themselves as the rightful rulers of other races. Even the esteemed Egyptians received such disregard.

By voicing the Greeks’ belief in their fundamental superiority, Aristotle justified an already existing system of enslaving other tribes through force and war. Many were the citizens who had numerous slaves who toiled for them in the field and in the house alike. The whole economic system of ancient Greece relied on slaves for its well-being. Aristotle even claims that those who are born to slavery are physiologically different from those born for freedom:

Nature would like to distinguish between the bodies of freemen and slaves, making the one strong for servile labour, the other upright, and although useless for such services, useful for political life in the arts both of war and peace.

However, although he is probably the most influential Greek philosopher, Aristotle never completely dominated the philosophical sphere. Other philosophers also touched upon the subject of slavery, some making humanitarian claims for freedom and equality long before Humanitarianism was conceived. These detested the notion that sheer strength and the power to inflict harm on another justifies subjection and enslavement.

Others, more radical than Aristotle and less considerate of the rights of slaves (Aristotle himself treated his slaves kindly) claimed that superior force implies superior virtue, and it is therefore both just and natural to enslave others by strength. While Aristotle does not deny that some, but not all, are natural rulers, and later in the work professes his political beliefs that the virtuous should rule over the less-virtuous, he attempts to settle the discussion thus:

We see then that there is some foundation for this difference of opinion, and that all are not either slaves by nature or freemen by nature, and also that there is in some cases a marked distinction between the two classes, rendering it expedient and right for the one to be slaves and the others to be masters: the one practicing obedience, the others exercising authority and lordship which nature intended them to have. The abuse of this authority is injurious to both; for the interests of part and whole, of body and soul, are the same, and the slave is a part of the master, a living but separated part of his bodily frame. Hence, where a relation of master and slave between them is natural they are friends and have a common interest, but where it rests merely on law and force the reverse is true.

When observed through such a prism, one which was all but a convention in Aristotle’s time, slavery becomes an acceptable and necessary system. It allows enslavement through force but advises against it, regarding slaves as a fundamental part of any household and one with which citizens should work in harmony.

Aristotle’s treatment of his own slaves, and historical relations of other such persons whose slaves were loyal and happy, show that Aristotle’s ideas of harmony and kindness towards slaves did in fact have their manifestation in reality. That those slaves would have been happier still in liberty was disregarded on the basis of a claim to superiority alone.

Curiously enough, there have been many cases of successful and ingenious slaves in antiquity whose character was so far from inferior as to lead to their release. One example is of course the Roman playwright Terence, one of the greatest and most famous playwrights of the ancient world who began his career as a slave and was later freed for his skill. Another example is Cicero’s assistant, Tiro, who developed the Tironian shorthand and was a prolific writer. Like Terence, Tiro was liberated by his master.

Slavery in Modernity

Although slavery had run a long course, so long as to be but a short time gone from western civilizations, it was bound to die out in the modern era. The French revolution, the change towards the humane in philosophical movements, the rise of democratic governments and policies – the west has been progressively moving towards the end of slavery since the end of the middle ages.

The most famous case of slavery is of course that of black slaves in America. I dare say it is those slaves alone who enter the minds of most of the readers of these lines whenever the word ‘slavery’ is pronounced. Indeed, its monopolization of the discourse on slavery as a subject is far from surprising. It ended dramatically, and its influence is remembered and borne to this day by a black community of the United States.

The case of black slaves has also made its mark on the literary world. The most notable book written on the subject is of course Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but there have also been numerous biographies of escaped slaves. Solomon Northup’s case for example, as told in his memoirs 12 Years a Slave has also had its impact. Its narrative is curiously linked with that of the former.

The face-to-face encounter with the humans behind the slave industry in an age of democratic awakening had left its mark. The emotional and often eloquent accounts of escaped slaves blurred the lines between “superior white humans” and “inferior” slaves.

To that were added two reinforcements. Firstly, import of slaves from Africa had dwindled, leaving a void which was easily filled with slaves born on American soil, thus bringing slaves closer to citizenship. Secondly, the lasting division between northern countries, in which people of colour were free from birth, and southern countries in which slavery was supported by law, provided an alternative way of thought which would eventually prevail.

Protests against the inhumane custom could be heard louder and clearer by each passing season. As Northup’s eventual liberator tells the poor slave’s master: “I would say there was no reason nor justice in the law, or the constitution that allows one man to hold another man in bondage. It would be hard for you to lose your property, to be sure, but it wouldn’t be half as hard as it would be to lose your liberty.”

By the time of the Civil War such professions were far from uncommon. A new mode of thought was slowly taking over in the place of conservative traditions. The voices justifying whipping as a necessity, claiming that the slaves were better off than the free black folk of northern states and relying on the Bible for justification were no longer dominant. Instead, other voices were heard, like that of William Cowper:

Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone

To reverence what is ancient, and can plead

A course of long observance for its use,

That even servitude, the worst of ills,

Because delivered down from sire to son,

Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing.

But is it fit, or can it bear the shock

Of rational discussion, that a man

Compounded and made up, like other men,

Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust

And folly in as ample measure meet,

As in the bosom of the slave he rules,

Should be a despot absolute, and boast

Himself the only freeman of his land?

And thus democratic ideals had eventually won over conservative and utilitarian thought. The story of slavery in the United States famously ended with the roar of the Civil War, but the end of that era was but the first note in the black community’s struggle for equal rights and an end to legal segregation. Both struggles have rightfully left the community with bitter sentiments. Its eventual acceptance into the leading western society of the modern world, albeit still partial and wanting improvement, rendered the notion of slavery unthinkable in modern minds.

I wish to revive to some extent that lost notion. Humane and democratic values, alongside the final ordeal of the black slaves in the United States, have left humanity quite blind to what it had lost in the bargain of relinquishing slavery. I am not talking about slavery as a cheap working-force to be preserved for the benefit of the few. Nor do I support slavery and wish it to return. And yet, much has been lost alongside slavery. It is that loss which I will attempt to illuminate.

Slavery as a Beneficial Institution

It is here, reader, that I require your greatest attention. Two questions come to mind when dealing with this subject, both of which pertain to the broadest and most rooted norms of our societies. Firstly, do ends justify means? Secondly, which leading principles have changed alongside the banishment of slavery? I find them both curiously entwined.

And so, let us begin with the question of ends versus means. It has lamentably become a grotesque rhetorical question. I for one was taught as a child, by stern moralizing teachers, that an end never justifies its means. There is a terrible social consensus surrounding the question. Every historical atrocity which was committed on the basis of an ideology which differs in the slightest from current standards is immediately thrown into the formula, and of course becomes unjustifiable. Nowhere is it more substantial than in the example of the Holocaust.

It is not homage to Godwin’s law which makes me bring up the Third Reich, but a sincere belief that the memory of the Holocaust eradicated any possibility of genuinely discussing the subject, allowing modern society to write “Ends don’t justify means” on its banners. The Holocaust is the last and largest straw which broke the back of older notions. Some of its results are today’s dreadful culture of political correctness and Europe’s inability to deal harshly with violent immigrants*.

*I am of course not implying that all immigrants are violent, but many of those who have shown violence have received mild treatment.

The wrongdoings of the Holocaust are indeed beyond expression. To name it cruel and inhumane is an understatement, and I would be the last to claim that in this case the end justified the means. And yet, does one instance of an end not justifying the means rule out the possibility of any end justifying any means? I think not, and yet it is slowly becoming a reality.

Does order justify lying, as Socrates suggests? Does security for the many justify the incarceration of those who have threatened that security? Do transportation and trade justify a certain amount of pollution? Perhaps some would answer these questions negatively, but in general I think most would agree that these ends justify their means, for the very shape of our societies relies upon them. It is our task as a society to map our desired goals and reach them with the means which are at our disposal, unless we decide that that means is unjustifiable.

This brings us back to slavery. Slavery is quite obviously the means, and one unsuited for many ends – the luxury of the few, economical advantages etc. It is these ends which are often considered when dealing with slavery as a means. However, many writers argue that the true end of slavery is culture and liberty.

Only with the aid of slavery were the people of ancient societies free to deal with politics and hold intellectual gatherings, whereas today both politics and intellect have become nothing more than trades. Politics is of course corrupted beyond redemption, its sphere has long ceased to be a meritocracy. The case of science is less lamentable, but even science is now bordering industrialism. In the days of slavery those who dealt with culture and kneaded it into shape were free from carnal worries. In a society led by wealthy and unworried intellectuals, no wonder the thing most cherished became Virtue.

It is precisely the esteem of Virtue that we lack. Today, what is infinitely more revered and desired than Virtue is Wealth. For wealth is in truth freedom, it provides one with the ability to mould one’s fate. We must admit it to ourselves that, as things stand today, few are the persons who can claim true freedom. I am not referring to constitutional freedoms, but to independence. How many of you and your peers are free to direct their own lives? Who can truly do as they please, unbound by financial obligations or reliant on a job from which retirement is impossible? As Rousseau says:

What then? Is liberty maintained only by the help of slavery? It may be so. Extremes meet. Everything that is not in the course of nature has its disadvantages, civil society most of all. There are some unhappy circumstances in which we can only keep our liberty at others’ expense, and where the citizen can be perfectly free only when the slave is most a slave. Such was the case with Sparta. As for you, modern peoples, you have no slaves, but you are slaves yourselves; you pay for their liberty with your own. It is in vain that you boast of this preference; I find in it more cowardice than humanity.

By selling our time to employers we do but sell a portion of our lives. We are slaves to a minor extent, and worse still – trapped in Plato’s cave, so that most are unaware of their situation. Horace’s slave confronts him in Satires: “Are you my master, you that are slave to so many persons and things?”. Two millennia later the question is all but more relevant.

In such a society Virtue can no longer thrive. In the absence of the original, we have fallen to worshipping the substitute. Were we truly free we would have esteemed Virtue over Wealth, as the Romans did. The absence of estimation for Virtue has caused the virtual extinction of people of character. Extraordinary people are no longer renowned or admired. Instead, the new paragons of society are the wealthy and unvirtuous. Alongside trading slavery for democracy, we have traded Cicero for the Kardashians and Charlemagne for Trump.

What then is to be done? Should slavery be legitimized once more, as a remedy to the ills of modern civilizations? Absolutely not. We must simply discern between relinquishing the means and relinquishing the end – only does not necessitate the other. The slavery of humans can be supplanted by machinery. As Wilde puts it:

The fact is, that civilization requires slaves. The Greeks were quite right there. Unless there are slaves to do the ugly, horrible, uninteresting work, culture and contemplation become almost impossible. Human slavery is wrong, insecure, and demoralizing. On mechanical slavery, on the slavery of the machine, the future of the world depends.

Yet regardless of how developed we become, we shan’t maintain our liberty unless we focus upon it. Becoming disenchanted with wealth and aiming for self-betterment, perhaps for Wordsworth’s “plain living and high thinking”, requires sobriety. It is only by realizing what we have lost in the bargain that we can strive to retrieve it by other means. Only when Virtue redeems its throne from the usurping Wealth will extraordinary persons appear to culturally lead us once more.

But should we abstain from striving towards that end, no amount of development would save us. Hyper mechanical development can lead to a society of philosophers just as easily as it can lead to a society of fools. I believe I need not point the way in which we’re headed.