Regard not then if wit be old or new,

But blame the false, and value still the true.

Anglican Christians distinguish three pillars of their faith: Reason, Tradition, and Scripture. An orthodox Christian might choose, in a rather Demosthenesean fashion, to retort with ‘Tradition, Tradition, and Tradition.’ Indeed, tradition seems to be paramount in all streams of orthodoxy, and yet the average orthodox Christian seems to be far more adept in reasoning through their beliefs than most other followers.

I was therefore not surprised to see Jonathan Pageau, one such Christian, provide a scintillating defence of his worldview in a recent interview; I was still less surprised to hear his response, when asked for his default source of wisdom: that he consulted with tradition for that purpose. What better way to summarise the Weltanschauung of the orthodox?

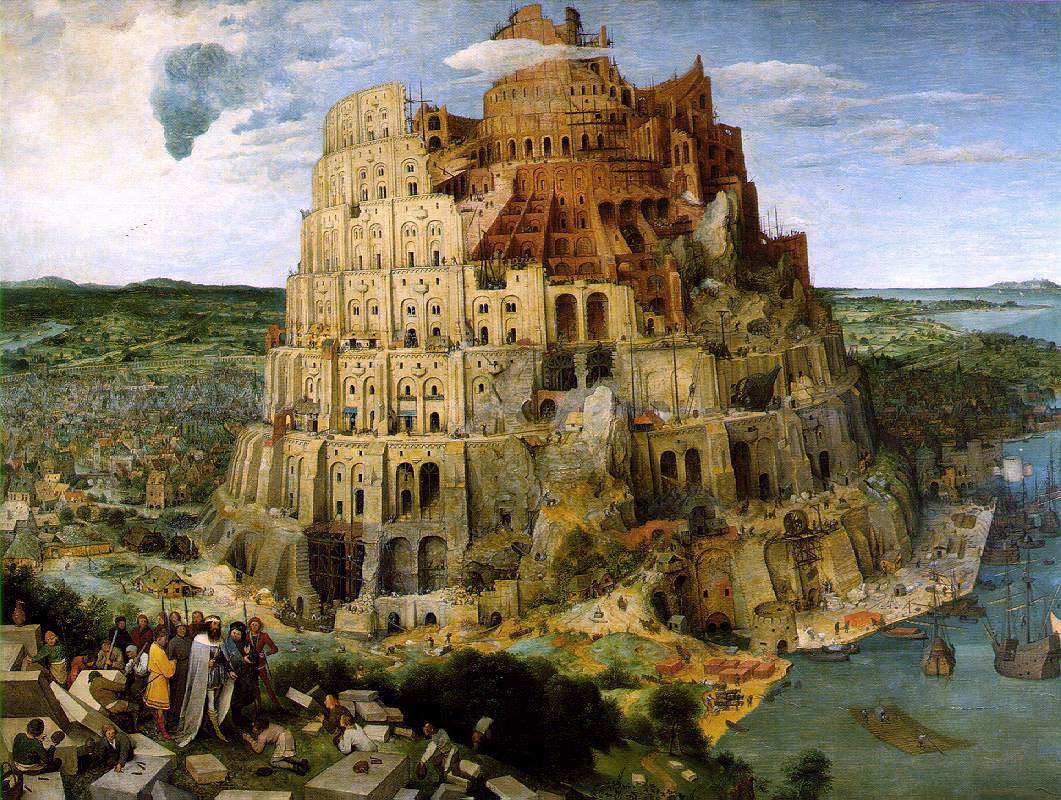

While appealing to tradition as a higher source of wisdom is tenable to a degree, this position does not stand the test of logical scrutiny. The most obvious problem with traditional wisdom is the inevitable infinite regression inherent to it; after all, what is now treated as tradition was introduced at some point, before which a different approach reigned supreme. Therefore, even the staunchest proponent of tradition will have to admit that humanity has brought about improvements in one form or another, indicating that some pieces of wisdom have appeared through innovation. Clearly, some process of selection is at hand, with the wise possessing the ability to identify wisdom regardless of its source, and so only a fool would posit that wisdom comes exclusively from tradition. Wisdom is never learnt, only ratified.

Nevertheless, the presence of pieces of wisdom in tradition is undeniable. Tradition has two main pillars to lean on in this regard: firstly, it represents the collective learning of large groups of people. The larger the number of people weighing in on a question, the more opportunities for correction and improvement occur. The abundance of wise adages and proverbs is therefore not surprising; these sagacious sayings capture important learnings that people usually miss on their own.

Secondly, proponents of tradition enjoy the benefit of relying on a posteriori reasoning; at the very worst, appealing to tradition will maintain the tried-and-tested status quo. In his book Collapse, Jared Diamond recounts how a group of European agronomists raised an eyebrow when they saw how New Guinean farmers installed their drainage pipes: perpendicularly to the slope, rather than parallel. Apparently, the farmers couldn’t justify this decision and they were easily influenced by the agronomists to reinstall the pipes as per the European fashion. Soon enough, the wet New Guinean climate caused water to accumulate behind the horizontal pipes, leading to devastating landslides. By simply relying on tradition, the farmers would have outsmarted the modern agronomists without even understanding the reasoning behind their practices. This example points to the principle of Chesterton’s Fence, which can be summarised as ‘if you don’t know why something exists, don’t change it.’ Fittingly, tradition captures this principle with the adage ‘better the devil you know.’

But here we reach the limitations of tradition: in many cases, people only realise the appositeness of a proverb in hindsight, as with the poor New Guinean farmers, indicating that mere acquaintance with a saying is insufficient. To fully understand a proverb, one must first fail to follow it. And these crystalised forms of traditional wisdom suffer from yet another problem: corruption. Perfectly good proverbs are often known only in their distorted form. Sometimes, the change doesn’t completely ruin the saying, leaving us with a bit of retained wisdom. ‘The early bird gets the worm’ is generally applicable, even if the full saying warns us that circumstances matter by adding that ‘the second mouse gets the cheese.’ But often we find the corrupt version of the proverb conveying a completely opposite meaning, as with ‘blood is thicker than water’ or the ridiculous excuse ‘it’s just a few rotten apples.’ Even aphorisms aren’t safe from tampering: I’m yet to see anybody claiming the world as their oyster while alluding to ravin.

The faulty way in which people draw from corpus of tradition is best exemplified in the inconstant interpretation of the messages and desires of Jesus. As Albert Schweitzer noted, each generation sees Jesus through its own lens. In our times, socialists may emphasise Jesus’s poverty and communal support, while United States Republicans often argue that Jesus favoured ‘small government.’ The changing judgement of Jesus’s mood and intentions can be traced back even to early Christianity, with texts experiencing de-apocalypticisation and biblical authors depicting extremely different versions of god. One need only compare the god of Revelation to the forgiving god portrayed by Jesus to notice the negligible effect that supposed teachings make on the mind of the intransigent. As Rousseau expresses the matter in his confessions: “Men, in general, make God like themselves; the virtuous make Him good, and the profligate make Him wicked; ill-tempered and bilious devotees see nothing but hell, because they would willingly damn all mankind; while loving and gentle souls disbelieve it altogether.”

We can identify another limit by pointing out that the collective opinion of people does not suffice for accurate judgement. Had this observation been incorrect, such concepts as the miasma theory would not have existed and markets would have been closer to complete efficiency. Of course, the very existence of different religions attests to the endless potential of groups for folly and delusion.

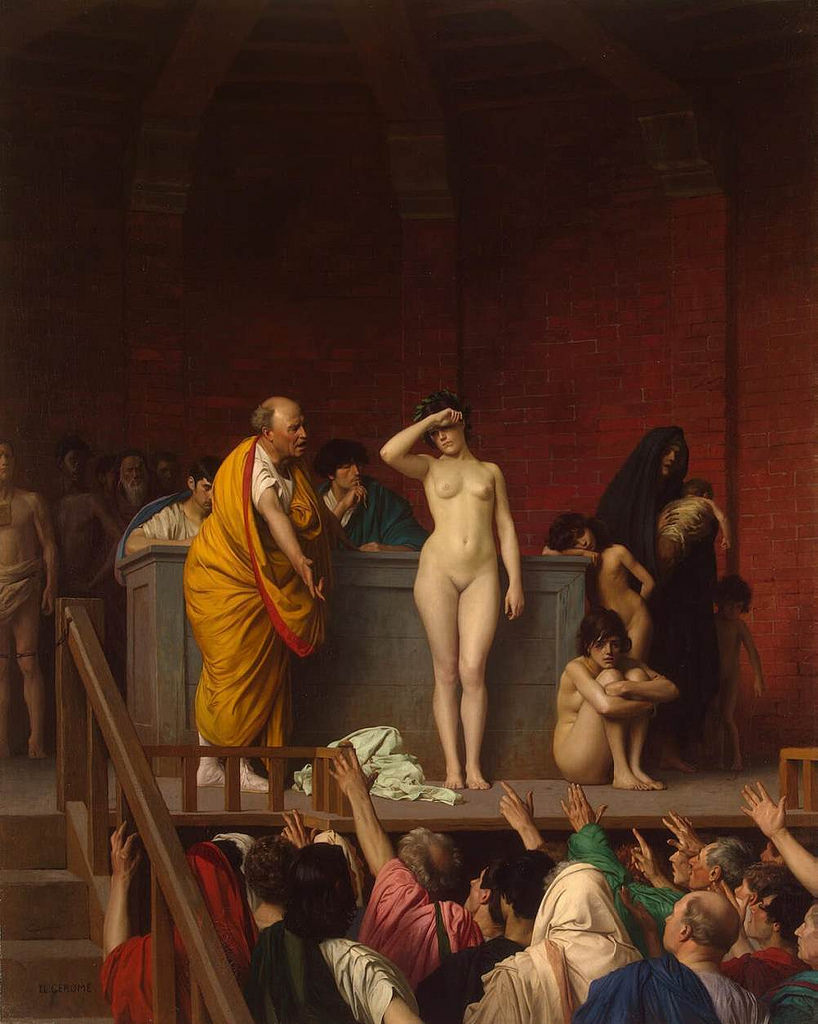

In practice, the adoration of tradition is a corruptive force of its own, constraining social and moral reasoning according to norms that may no longer be applicable, promoting a procrustean and repressive society, and ossifying bits of past wisdom in a way that misses the pith for the rind. This penchant for blind conservation leads, in its extreme form, to the quibbling that forms the mainstay of the entire field of theology.

What, then, is wisdom? I believe that this question is insoluble. We may coin gnomic sayings to try capturing some elements of wisdom, and I propose the following epigram for that purpose: wisdom is realising that people mistake knowledge for intelligence. We may also, ironically, borrow a page from Christian orthodoxy and address this issue apophatically; I’ve tried doing so once, to no great success. But these attempts will invariably fall short of answering our question.

For the meanwhile, we can safely conclude that tradition is not worthy of the valorisation it often receives. Wisdom is independent of tradition, for without its possession we would not be able to identify the wisdom of our predecessors. Nevertheless, the second form of wisdom is certainly abundant, and so, to use a final proverb, let us not throw the baby out with the bathwater.